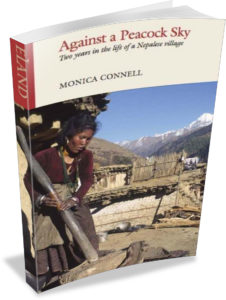

Monica Connell stops by Travel Writing World again, this time to answer a few questions about her career as a writer. She is the author of several books including Against a Peacock Sky: Two Years in the Life of a Nepalese Village (Eland 2014) and most recently Gathering Carrageen (Sandstone 2015), a memoir about her time in Ireland.

How did you first become interested in writing travel books?

I was studying Anthropology at Oxford University and went to a remote village in north-west Nepal to do the fieldwork for a doctorate. The idea, at that time, was that anthropologists live in a place for at least two years, learning the language and participating as much as possible in daily life. Those two years changed me deeply and I realized I no longer wanted to force everything I’d experienced into the straightjacket of an academic thesis. I wanted to write about my relationship with the family who shared their home with me, I wanted to describe the weather, the landscape, the seasons, my own emotions, and the difficulties I encountered—all of which would have been irrelevant to a thesis. So I left the University and wrote what eventually became a travel book

How did you manage to get your first travel book published?

How did you manage to get your first travel book published?

At first, I had a lot of rejections, many publishers saying the book fell between categories being neither conventional travel writing, nor memoir, nor anthropology. But amongst the rejections, there was enough encouragement to keep me trying. In the end, I found an agent who secured me a contract with Penguin not only for this book but for a second one yet to be written.

What is your writing process like, both on the road and at home? And how long does it take you to write a book inclusive of the research, travel, writing, and editing phases?

My first book took about ten years: one researching and learning Nepali, two-and-a-half in the village in Nepal, and about seven writing—including working out how to structure the book and finding a voice. I made notes in the village, in a book that became so black from filth and smoke, I could hardly bear to look at it when I got home. I tried using a voice recorder but found it intrusive. Photos were invaluable for visual memories. Prose style is important to me and I build my books slowly, paragraph by paragraph, hoping to transport the reader to the situation I’m describing through language and rhythm. I rarely do second drafts and edit minimally.

What travel books or travel authors influence or inform your own work?

John Berger’s Pig Earth and Once in Europa. What inspires me most about them is that, although their intention is to ‘document the eclipse of peasant culture’ in Europe, they are novels. I started to wonder if an artistic approach might convey an extra dimension—emotional perhaps—that is often lacking in travel writing. Both my books read as collections of short stories. I have also enjoyed Robyn Davidson, Geoff Dyer, Peter Matthiessen, Norman Lewis, and Dervla Murphy.

What advice would you give to someone interested in writing a travel book?

Go with an open mind. Let the experience come to you rather than shaping it with your own preconceptions, or an agenda you want to fulfill. Learn at least some of the language. Treat everyone you meet, their culture and beliefs with respect, even if you disagree. Don’t be daunted by publishers’ rejections — a submission one publisher hates, another may love.

What is so appealing about the travel book as a literary form?

It confuses genres, shifting between memoir, documentary, fiction, narrative non-fiction, and —why not? — poetry.

Why write about travel?

Travelling, especially if you stay in one place for a long period of time, is a humbling experience. You learn the relativity of many of the values and much of the conditioning you have never questioned. For both writers and readers, understanding and empathizing with other cultures is surely the basis for a kinder, more humane, world.

Monica Connell is the author of Against a Peacock Sky: Two Years in the Life of a Nepalese Village and most recently Gathering Carrageen (Sandstone 2015), a memoir about her time in Ireland.

But, for me, these physical hardships were nothing compared to the emotional ones. Before we arrived many of the villagers had never seen foreigners, let alone white ones, so their curiosity was understandable, but I was occasionally reduced to tears when groups of people gathered round us pointing and laughing, reaching out to touch us and talking about us as though we were animals in a zoo. Then, there was the local conviction that we were doctors and had infinite supplies of medicine. It was useless trying to convince people that they needed to go to the hospital (the nearest health post) a day’s walk away, so we did our best with a medical manual and the medicaments we had brought with us and later replenished. But I shudder now to think of the terrible injuries and afflictions that people we knew and cared about trusted us to cure.

But, for me, these physical hardships were nothing compared to the emotional ones. Before we arrived many of the villagers had never seen foreigners, let alone white ones, so their curiosity was understandable, but I was occasionally reduced to tears when groups of people gathered round us pointing and laughing, reaching out to touch us and talking about us as though we were animals in a zoo. Then, there was the local conviction that we were doctors and had infinite supplies of medicine. It was useless trying to convince people that they needed to go to the hospital (the nearest health post) a day’s walk away, so we did our best with a medical manual and the medicaments we had brought with us and later replenished. But I shudder now to think of the terrible injuries and afflictions that people we knew and cared about trusted us to cure.